©Yosuke Kashiwakura α7R, Zeiss Sonnar T* FE 55 mm F1.8 ZA, F1.8, 1/5000 s, ISO 800

Vol.1

03/25/2024

Encounters on the island and reflections as a photographer

Yosuke Kashiwakura, Nature Photographer

Thinking together about the global environment through interviews with creators working on environment. Yosuke Kashiwakura, a nature photographer conveys the beauty of nature and a message about protecting the global environment such as natural landscapes, flora and fauna as his subjects. He explores the connection between photographers and sustainability through stories from his experiences on Borneo and Rebun Islands.

Yosuke Kashiwakura

Nature Photographer

Born in 1978. He is based in Kanagawa prefecture and Rebun Island in Hokkaido, Japan, and captures the natural landscape. His works have been exhibited at venues such as the U.S. Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, the Natural History Museum, London, and the conference of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. He has won major international photography awards from National Geographic’s international photo contest, Wildlife Photographer of the Year, and LensCulture. In March 2024, he published a documentary photo book of orangutan orphans on Borneo Island, Back to the Wild: The Orangutans Who Lost their Forest.

Environmental devastation witnessed on Borneo Island

What made you decide to consciously take photos of the natural environment?

More than 15 years ago, I participated in a tour for a magazine photo shoot of Borneo Island, an island in Southeast Asia, organized by an environmental conservation group. I photographed orangutans, elephants, proboscis monkeys, and other animals that appeared in nearby forests as I rafted down the Kinabatangan, a long and famous local river. I enjoyed taking pictures so much that the president of an environmental conservation group approached me and asked, “Do you know why so many animals turn up here?” I was unable to answer that question. Then, I was told that people had built palm oil plantations on the other side of the forest that stretched to the end of the land. He told me wild animals were being driven into the forests that are left behind, which was why the density of animals was so high that I could take pictures of them together.

After hearing these words, I felt extremely embarrassed to have been taking pictures with such excitement. I still remember how I felt at that time. I then came to question whether I had really made the right choice as I had been taking pictures of only attractive subjects. The next day, we visited the Orangutan Rehabilitation Center, where orangutan infants were cared for after having lost their mothers. Due to deforestation was struck by the sight of orangutans being patiently trained by humans to return to the forest again. This is what inspired me to continue photographing these infants as my subjects because I felt that I needed to take action to support them. When we asked for permission to take pictures in the facility on a long-term basis, the president of the environmental conservation group helped me to obtain permission. So, I stayed with the orangutans for about a month, taking pictures of them.

Have you discovered anything new since you started taking pictures of orangutans?

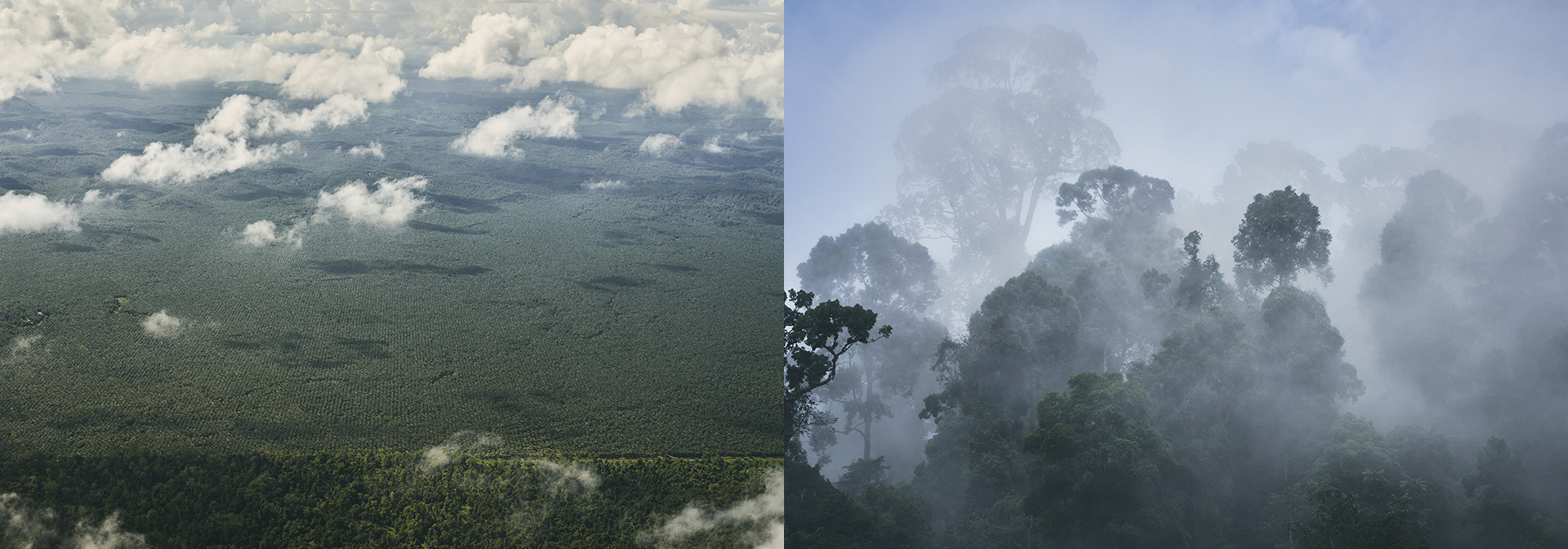

The rainforest on Borneo Island, which had been called a treasure trove of biodiversity, has nearly disappeared. In its place are palm oil plantations stretching as far as the eye can see. So, the animals that used to live there had no place to go. These orangutan infants were forcibly removed from their mothers when the rainforest was destroyed. Typically, orangutan infants cling to their mothers’ bodies to learn what their parents eat and how to survive in the treetops while protecting themselves from predators. However, infants cannot learn how to live in the wild without their mothers. So, they can only recover their ability to live in the forest through training at the Rehabilitation Center. On top of this are environmental changes due to climate change. So, the plight of endangered species is likely to get even worse.

What are your plans for informing the world about what is happening on Borneo Island going forward?

Now, the forests around the world are disappearing. On Borneo Island, there are palm oil plantations stretching far beyond the horizon, which, to me, is a very destructive landscape. I came to believe that this activity was like a tsunami. The human-made palm oil plantations have slowly proceeded inland like a tidal wave, and the tropical forests have vanished. Calling this process “Green Tsunami,” I take pictures of this horrifying view to once again remind everyone of the impacts that deforestation may bring.

Learning the value of being grateful for things as they are through the island of Rebun

How did you encounter your other base of operations, Rebun Island?

It all started when I hiked up Rishiri Fuji on Rishiri Island with Kanae Minato, a novelist and the original author of Kita no Kanaria-tachi [A Chorus of Angels], a movie set on Rebun Island. When Minato said, “The neighboring island of Rebun is also wonderful,” I was intrigued and went to visit there at a later date. While hiking up on the northernmost observation deck of Rebun Island, I turned around and was struck by a stunningly beautiful view that made me fall in love with the island. I discovered that there was a community in the area, so I was hoping that there might be a vacant residence there. After searching for vacant houses online, I found that there was only one vacant house in the community. Afterward, the owner of the house transferred it to me, so I renovated it myself and built a base of operations for life and photography on Rebun Island.

On Rebun Island, what is the theme that you are capturing?

Initially, I wanted to keep it to myself and just take my time capturing the scenery. But the starry sky is unbelievably beautiful, and the daytime scenery is so simple and picturesque. Gradually, I came to want to share their beauty and create an International Dark Sky Place*. Rebun Island contains more than 300 species of alpine plants that bloom, but it seldom attracts visitors except in spring and summer. I hope that all kinds of people will visit this place throughout the year and that it will turn into a place where they can just look up at the starry sky in tranquility. There may be concerns about the impact on nature and over-tourism if more people visit the area. So, my goal is to consider how to build an environment where humans can coexist with nature.

Can you describe your motivation for working to create an International Dark Sky Place?

Since so many buildings have been built across the country that have filled the city with lights brighter than the stars, we have lost sight of the stars in the sky, haven’t we? Starry skies will return simply if we control the direction of the lights. We are seeing a movement to create new theme parks to support the regional economy. But I think it’s more important to restore what was there originally. I think every city will be attractive once we pin down the local beauty of the location, even if there is nothing new built. I want the value to shift toward appreciating things as they are.

It is reported that young people are especially interested in environmental issues and sustainability. In light of your work, is there any advice you would like to share about how individuals can make contributions?

I have been searching for something I can do with young people. I think back to my hometown, the fields and the mountains behind my house, and the original landscapes that I treasure. Being involved in the grand global environmental movement is also important, but what we can readily do is to understand what is going on in local area and to protect it properly. As the number of such people increases to 100, 10,000, and 1,000,000, the environmental conservation effort will expand to a remarkable scale.

How would you like to promote the importance of the global environment in your future activities?

I want to interview adventurers, explorers, and nature guides who encounter the changes in the global environment. I want to present their unfiltered voices and expressions as they talk about the global environment. I’m curious to hear what people who live on the front lines of global environmental change really think. * A certificate is given to the locations that have made outstanding efforts to protect and preserve dark, natural night skies, free of light pollution.

©Yosuke Kashiwakura α7R II, FE 100-400mm F4.5-5.6 GM OSS, F11, 1/800 s, ISO 800